Abstract

IgE not only provides protective immunity against helminth parasites but can also mediate the type I hypersensitivity reactions that contribute to the pathogenesis of allergic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis. Despite the importance of IgE in immune biology and allergic pathogenesis, the cells and the pathways that produce and regulate IgE are poorly understood. In this Review, we summarize recent advances in our understanding of the production and the regulation of IgE in vivo, as revealed by studies in mice, and we discuss how these findings compare to what is known about human IgE biology.

Key points

- The production of IgE and its clearance from the blood are tightly regulated, which results in transient IgE antibody responses and the maintenance of low steady-state levels of IgE.

- IgE can be generated by a direct class-switch recombination pathway from Sμ to Sε, by a sequential class-switch pathway from Sμ to Sγ1 followed by Sε, as well as by a recently described alternative sequential class-switch pathway from Sγ1 to Sε, which then joins to Sμ. Additional work is needed to better understand the contribution of each class-switch pathway to IgE production in health and disease.

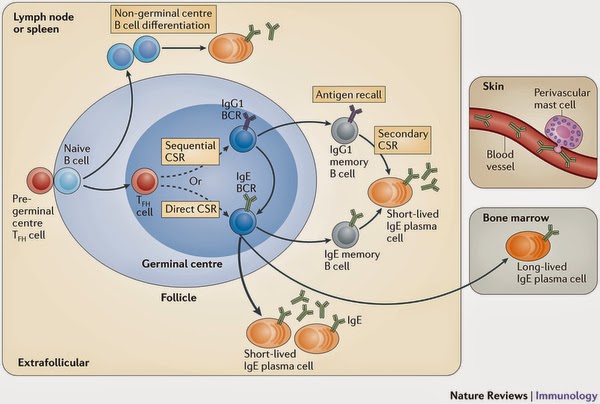

- Early IgE antibody responses arise from extrafollicular sources, whereas later IgE responses are derived from germinal centres. IgE germinal centre responses are transient, which may limit IgE production.

- IgE plasma cells that are derived from germinal centres are predisposed to be short-lived in contrast to IgG1 plasma cells that are derived from germinal centres, and are primarily long-lived.

- IgE memory responses can arise from both IgE memory B cells and IgG1 memory B cells, but the contribution of each memory B cell subset to total IgE memory responses remains to be clarified.

- The high-affinity Fc receptor for IgE (FcεRI) on dendritic cells and macrophages, but not on mast cells or basophils, contributes to the clearance of serum IgE. By contrast, the low-affinity Fc receptor for IgE (FcεRII; also known as CD23) on B cells does not contribute to the clearance of serum IgE, but modulates total serum IgE levels by providing a sink that binds a substantial portion of the total IgE pool.

- A better understanding of IgE biology may lead to new approaches to treat IgE-driven allergic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis.

Introduction

IgE mediates type I hypersensitivity reactions, which include both systemic and localized anaphylaxis1, 2. Although IgE constitutes a first-line defence against parasites such as helminths, inappropriate IgE-mediated immune responses to normally innocuous environmental antigens can contribute to the pathogenesis of allergic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis, and can lead to severe life-threatening anaphylaxis.

IgE (Fig. 1) is the immunoglobulin isotype that has the lowest abundance in vivo and its levels are tightly regulated. Concentrations of free serum IgE are ~50–200 ng per ml of blood in healthy humans compared with ~1–10 mg per ml of blood for other immunoglobulin isotypes; a similar proportion of immunoglobulins are also present in mice3. In addition, the serum half-life of IgE is the shortest of all immunoglobulin isotypes, ranging from ~5–12 hours in mice to ~2 days in humans, compared with ~10 days in mice and ~20 days for IgG in humans3. Furthermore, serum IgE responses in mice are typically transient and robust long-lived IgE responses are generally not observed4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Taken together, the low steady-state level of serum IgE and the transient nature of IgE responses may help to minimize IgE cross-reactivity that could trigger unwanted anaphylaxic reactions.

IgE binds to IgE receptors on immune cells in the tissues and in the circulation. There are two receptors for IgE: the high-affinity Fc receptor for IgE (FcεRI) and the low-affinity Fc receptor for IgE (FcεRII; also known as CD23)1, 11, 12 (Fig. 1b). FcεRI is expressed by mast cells and basophils, on which its activation mediates cellular degranulation, eicosanoid production and cytokine production12. In humans, FcεRI is also expressed by dendritic cells and macrophages, on which its activation mediates the internalization of IgE-bound antigens for processing and presentation on the cell surface, as well as the production of cytokines that promote T helper 2 (TH2)-type immune responses12. FcεRII is expressed by B cells, on which it regulates IgE production and facilitates antigen processing and presentation. FcεRII is also expressed by other cells such as macrophages and epithelial cells, on which it mediates the uptake of IgE–antigen complexes11.

Despite the importance of IgE in helminth immunity and allergic pathogenesis, the pathways by which IgE is produced and regulated are poorly understood. Extensive studies of the production of IgG1 in mice have delineated an early extrafollicular phase, in which short-lived plasma cells that produce low-affinity antibodies are generated, followed by a germinal centre phase, in which memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells are generated that produce high-affinity antibodies13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. By contrast, it has been unclear whether the production of IgE follows a similar development path of B cell switching, antibody production and B cell memory as described for IgG1. The study of IgE production and regulation in vivo has been difficult because IgE B cells (that is, B cells that have undergone class-switch recombination and that express an IgE B cell receptor (BCR)) and IgE plasma cells are found at very low frequencies. Another reason why it has been challenging to study IgE in vivo is because IgE B cells are difficult to specifically identify, as serum IgE binds to FcεRII on the surface of all B cells. However, the lack of sustained IgE responses in mice differs from the sustained responses that are frequently observed for IgG1 and this suggests that there are differences in the production of IgE compared with IgG1.

Recent studies in mice have provided new insights and have improved our understanding of how IgE is produced and regulated in vivo. In particular, the generation of three different IgE reporter mice (which have been termed M1 prime GFP knock-in mice9, 19, 20, Verigem mice10 and CεGFP mice21 (Table 1)), in which either transcription9, 19, 20, 21 or translation10 of membrane IgE is tagged with a fluorescent protein, has facilitated the direct and specific detection of IgE-switched B cells without complications from B cells that have serum IgE bound to FcεRII on their cell surface. In this Review, we summarize these advances, focusing on the B cell-intrinsic factors that regulate IgE class switching and production, the cellular aspects of IgE production and memory, the mutation and affinity maturation of the IgE antibody repertoire, and the clearance and homeostasis of IgE in mice. As a result of space limitations, we do not discuss the structure, the signal transduction or the biology of FcεRI or FcεRII in detail.

B cell-intrinsic factors

IgE class switching. Two main pathways of immunoglobulin class switching have been described for IgE: a direct pathway from the IgM to the IgE isotype and a sequential pathway from IgM to an IgG1 intermediate and then to IgE22, 23 (Fig. 2). Although sequential IgE class switching has been observed in several different studies (see below) (Box 1), the reported proportion of direct versus sequential IgE class switching that can occur in mice greatly differs between research groups.

|

| Figure 2: Direct, sequential and alternative sequential IgE class-switch recombination.

The mechanism of class-switch recombination to produce IgE involves both direct and sequential antibody isotype switching, which is the process by which the IgM constant region (Cμ) is exchanged for the downstream constant regions of IgE. a | The exons encoding each isotype constant region are preceded by an intronic promoter (arrow), a non-coding exon (I exon) and a switch region (S). The switch regions of IgM (Sμ), IgE (Sε) and IgA (Sα) are homologous to each other and the various IgG switch regions (Sγ) are highly similar to each other. Class-switch recombination typically involves the direct recombination of a donor Sμ region with a downstream acceptor switch region (for example, Sε), along with the deletion of intervening sequences, the ends of which are joined together in a reciprocal fashion to generate circular transcripts. Activation of intronic promoters (arrows) facilitates the accessibility of switch regions to undergo class switching97, 98, and DNA lesions that function as recombination points for class switching are generated in transcribed switch regions by the enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)99. Direct IgE class switching is a single recombination event between Sμ and Sε. b | Sequential class switching refers to a two-step recombination process in which Sμ is first joined to Sγ1, followed by joining to Sε. c | Alternative sequential class switching is a newly described pathway observed in mice that lack the core Sμ region (ΔSμ) in which Sγ1 is joined to Sε first, followed by joining to a small region upstream of Sμ that includes Iμ. All potential alternative sequential switch junctions and circular DNAs are depicted. 3′RR, 3′ regulatory region.

|

Box 1: Detection of direct and sequential IgE class switching

IgE class-switch history can be determined by several methodologies. IgE class-switch junction DNA can be directly amplified by nested PCR between the switch region of IgM (Sμ) and the switch region of IgE (Sε), using primers that are specific for the intron region of IgM (Iμ) and the constant region of IgE (Cε). Detection of a remnant of the switch region of IgG1 (Sγ1) in the amplified product indicates a sequential class-switch event. Alternatively, active class switching can be studied by analysing the circular transcripts or circular DNA containing the constant heavy chain94, 95, 96. During class switching, the intervening genomic DNA between two connecting switch regions is looped out, generating an episome in which the intronic promoter of the downstream switch region (that is, Iε or Iγ1) drives transcription of the constant region adjacent to the upstream switch (that is, Cμ or Cγ1). In the circular transcript assay, primers that are specific to Iγ1 and Cμ identify circular products from Sγ1–Sμ junctions, primers that are specific to Iε and Cμ identify circular products from Sε–Sμ junctions, and primers that are specific to Iε and Cγ1 identify circular products from Sε–Sγ1 junctions.

To analyse circular DNA, PCR fragments are obtained from DNA using similar primers. These PCR fragments will be heterogeneous unless the assay is carried out on a single cell. The circular DNA assay has limited sensitivity because only a single copy of circular DNA is generated in switched cells. In addition, subsequent deletions could occur in episomal DNA that do not reflect what might be occurring at the chromosomal DNA level. One caveat to the above methods for assessing class-switch history is that it is often difficult to distinguish productive from non-productive class-switch events. In addition, switch region repeats are often deleted as a result of PCR amplification or inherently during class switching, such that a lack of detection of sequential switch remnants may not indicate a lack of sequential class-switch history. Circular transcript and circular DNA analyses have been widely used to assess direct or sequential class switching, but they have not yet been applied to investigate alternative sequential IgE class switching.

Using different mouse strains in which IgG1 class switching cannot occur because of deletions of either the intron (Iγ1) or the switch (Sγ1) regions in the IgG1 locus (termed Δ5′Sγ1 mice24, 25 and Sγ1-knockout mice26, respectively (Table 2)), meaning that all IgE arises from direct class switching, two groups observed normal or increased IgE production in stimulated mature B cells compared with B cells from wild-type mice. In addition, there were no differences in the magnitude of IgE responses in wild-type and Δ5′Sγ1 mice that were infected with the helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis or that were repeatedly immunized with 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl conjugated to ovalbumin (NP–OVA)25. Furthermore, Sγ1-knockout mice showed comparable or higher IgE responses compared with wild-type mice following primary or secondary immunization with 2,4,6-trinitrophenyl conjugated to ovalbumin (TNP–OVA)26. Taken together, these data suggest that sequential class switching is not an absolute requirement for IgE isotype switching.

However, sequential IgE class switching can clearly contribute to IgE production in wild-type mice, as has been shown by multiple groups27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Recent studies indicate that direct and sequential IgE class switching may lead to distinct IgE fates. An analysis of the class-switch history of IgE germinal centre B cells and IgE plasma cells in CεGFP IgE reporter mice suggested that IgE germinal centre B cells had been primarily generated by direct class switching, whereas IgE plasma cells had primarily developed from sequential class switching21. In addition, in a separate study, the IgE antibody repertoire in wild-type mice was shown to have more somatic mutations and a higher affinity for antigens than that in mice that could not switch to IgG1, which suggests that sequential class switching promotes high-affinity IgE responses, whereas direct class switching may generate lower affinity IgE antibodies34.

Multiple factors can influence whether a B cell switches to IgE via direct or sequential class switching. Factors that are intrinsic to the switch regions, such as their size30, 37 and the distance of the IgE switch region (Sε) to the switch region of IgM (Sμ)38, can affect the frequency of class switching. Sε is the shortest switch region, it has fewer nucleotide repeats and is more distant from Sμ than from Sγ1 (Ref. 39). As a result, intra-Sγ1 recombination events occur more often than intra-Sε recombination events, which thereby limits class switching to IgE26, 30, 36, 40. The replacement of the core Sε region with a larger and more prominent Sμ region in mice (termed Sμ knock-in mice (Table 2)) resulted in increased IgE production30. This was associated with increased germline transcription of the IgE locus and increased direct class switching to IgE at the expense of class switching to IgG1, as the Sμ knock-in locus could outcompete endogenous Sγ1 for class switching. These studies suggest that the accessibility, the size and the sequence of the switch regions are a major determinant of IgE class switching.

The pathways of IgE class switching can also be differentially regulated in developing B cell subsets33, 41. Activated immature or transitional B cells preferentially switch to IgE versus IgG1 through direct class switching33. This may, at least partly, be due to differential methylation of the IgG1 promoter that leads to alterations in the efficiency of IgG1 and IgE germline transcription. Indeed, it has been suggested that this may be an explanation for the dysregulation of IgE production that is associated with several primary human immunodeficiencies, in which patients have impaired B cell maturation33.

Although the pathway for sequential class switching typically consists of switching from Sμ to Sγ1 followed by switching to Sε, an alternative sequential class-switching pathway has recently been reported in mice that lack the core Sμ region (Sμ-knockout mice (Table 2))36. Sμ-knockout mice have normal levels of IgE despite a severe defect in IgG1 class switching36. In these mice, Sγ1 first joins to Sε and then joins to recombination break points in a small region upstream of Sμ that includes Iμ (Fig. 2c). This alternative sequential class-switch pathway may be a mechanism by which sequential IgE class switching can occur without an IgG1 B cell intermediate stage, but this pathway has not yet been extensively studied in wild-type mice.

In humans, multiple groups have reported evidence for direct and sequential class switching to IgE at variable frequencies. Sequential class switching in humans may involve all Sγ regions, probably because of less stringent regulation of Iγ promoters than occurs in mice, in which sequential class switching mostly involves Sγ1 (supplementary information S1 (figure)). Sequential class switching to IgE has been detected in studies of human B cells that have been stimulated in vitro, with anywhere from 20%42 to 100%43 of Sμ–Sε junctions containing remnants of Sγ regions. In addition, direct analysis of IgE class-switch break points in unstimulated B cells from patients with atopic dermatitis or from patients who are infected with Schistosoma mansoni revealed that about 25% of Sμ–Sε junctions carried Sγ repeat remnants, which indicates sequential switching, with marked patient-to-patient variability44. However, other studies have found a dominance of direct class switching, with little or no evidence for sequential class switching. Remnants of Sγ regions were not observed in Sμ–Sε junctions from panels of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed human B cells45, and there was no evidence of sequential class switching in Sμ–Sε junctions of B cells isolated from patients with atopic dermatitis46.

Overall, these studies indicate that both direct and sequential class switching are involved in IgE production in mice and humans. The newly identified alternative sequential class-switch pathway needs further investigation to determine its relevance in wild-type mice and humans. Additional work is also needed to better understand the contribution of each class-switch pathway to IgE production in healthy individuals and to those with IgE-driven diseases.

The IgE BCR. Several studies have shown the importance of the membrane IgE BCR in primary and memory IgE responses. Mice that have a deletion of the transmembrane and the cytoplasmic domains of membrane IgE and that therefore lack expression of an IgE BCR (ΔM1M2 mice (Table 2)) completely lack primary and memory IgE responses47. Furthermore, mice in which the endogenous cytoplasmic domain of membrane IgE is truncated and replaced with the three amino acids Lys-Val-Lys, which results in a putative alteration of membrane IgE signalling and function (KVKΔtail mice (Table 2)), showed a substantial reduction in both primary and memory IgE responses47. These effects were specific to IgE responses, as IgG1 antibody responses in both ΔM1M2 mice and KVKΔtail mice were unaffected. These studies indicate that primary and memory IgE responses proceed through B cells that express an IgE BCR.

Mice in which the transmembrane and the cytoplasmic domains of membrane IgE are replaced with the corresponding regions of membrane IgG1 (KN1 mice (Table 2)) produced higher levels of IgE and had more pronounced memory IgE responses than wild-type mice, which is consistent with the studies using ΔM1M2 mice and KVKΔtail mice48. Thus, the cytoplasmic tail of membrane IgE influences the quality and the quantity of the IgE response, presumably through effects on the downstream signalling pathways, and limits these responses compared with the cytoplasmic tail of membrane IgG1.

Studies of the IgE gene locus in mice and humans revealed that the 3′-untranslated region of membrane IgE contains suboptimal polyadenylation sites compared with IgG1, which results in the production of a lower proportion of mRNA for membrane IgE than for secreted IgE49. It has been suggested that this contributes to lower expression levels of IgE BCRs on the surface of IgE B cells and that this may therefore provide an additional mechanism (along with the sequence of the cytoplasmic tail of membrane IgE) to limit membrane IgE BCR signaling.

The location of IgE production in vivo

Germinal centres give rise to high-affinity antibodies, long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells, whereas extrafollicular sites support the production of early low-affinity antibodies. The contribution of extrafollicular and germinal centre pathways to IgE production is poorly understood. Early studies in mice indicated that IgE B cells could be detected in lymph nodes50 and were localized in germinal centres51, but these studies may not have definitely distinguished bonafide IgE B cells from B cells that had serum IgE bound to their surface via FcεRII. Mice with monoclonal B cells and T cells were more recently used to study IgE production in vivo28, as these mice were previously shown to have greater IgE responses than wild-type mice. This study showed that, although IgE class switching occurred in germinal centres, only a small number of IgE germinal centre B cells could be detected.

Studies using IgE reporter mice have facilitated the clear identification and more detailed analyses of IgE germinal centre B cells: IgE germinal centre B cells have been detected in M1 prime GFP knock-in mice9, Verigem mice10 and CεGFP mice21 that were infected with N. brasiliensis, as well as in M1 prime GFP knock-in mice that were immunized with TNP–OVA9 and in Verigem mice that were immunized with NP conjugated to keyhole limpet haemocyanin (NP–KLH)10. In all three types of IgE reporter mice, it was found that the expression of the IgE BCR on the surface of IgE B cells was low.

One group10 developed a novel flow cytometry procedure using intracellular IgE staining to detect IgE B cells, which was not confounded by FcεRII-bound serum IgE and which had increased sensitivity in detecting B cells with lower levels of IgE BCR than surface IgE staining; they used this approach to confirm the presence of IgE germinal centre B cells in wild-type mice. The characterization of IgE germinal centre B cells in CεGFP mice confirmed that these cells had lower surface expression of the BCR, of the co-stimulatory molecules inducible T cell co-stimulator ligand (ICOSL) and OX40 ligand (also known as TNFSF4), and of the complement receptors CD21 and CD35, compared with IgG1 germinal centre B cells21.

The kinetics of IgE germinal centre B cell development during IgE responses have been studied in all three IgE reporter mice9, 10, 21, 52, 53. In contrast to IgG1 germinal centre B cells, which were shown to have sustained numbers in germinal centres, the number of IgE germinal centre B cells decreased over time in all three IgE reporter mice. Additional studies in Verigem mice (discussed further below) suggested that this was due to a predisposition of IgE germinal centre B cells to differentiate into short-lived plasma cells10. By contrast, studies using CεGFP mice suggested that the transient IgE germinal centre B cell response was due to reduced signalling through the IgE BCR and to a resulting predisposition of IgE germinal centre B cells to undergo apoptosis21. Thus, additional studies are needed to clarify the fate of IgE germinal centre B cells.

IgE can also be produced from non-germinal centre sources. Mice that are unable to develop germinal centres or that have greatly reduced germinal centre formation, such as mice that lack T cells, MHC class II molecules or B cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6), have higher levels of serum IgE than wild-type mice54, 55. In addition, immunoglobulin repertoire analysis of IgE germinal centre B cells and of IgE plasma cells from wild-type mice indicates that early IgE production is derived from extrafollicular sources, as almost all IgE plasma cells that were generated early following NP–KLH immunization contain unmutated germline sequences (and therefore are independent of the germinal centre), whereas IgE germinal centre B cells at the same time point contain mostly mutated non-germline sequences10. By contrast, IgE plasma cells that were produced late in the response to NP–KLH were shown to predominantly contain mutated non-germline sequences, which indicates a germinal centre origin of these cells10.

In humans, the extrafollicular or germinal centre origins of IgE B cells have not been well studied, although IgE B cells were detected in germinal centre structures in the lungs of a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis56. A major focus of studies of IgE production in humans has been to determine whether IgE can be produced locally in inflamed mucosal tissues in allergic diseases such as asthma and allergic rhinitis. These studies, which have been previously reviewed57, provide substantial evidence that IgE class-switch recombination and IgE synthesis can occur locally in nasal and bronchial mucosal tissues.

Taken together, early IgE antibody responses arise from extrafollicular sources, whereas later IgE antibody responses are derived from germinal centres. IgE germinal centre responses are transient compared with IgG1 germinal centre responses and this may limit IgE production.

IgE memory

Immunoglobulin memory consists of sustained antibody production from long-lived plasma cells that are found in the bone marrow and from the re-activation and differentiation of memory B cells following a secondary encounter with the same antigen. Recent studies have considerably increased our understanding of the origin and the lifespan of IgE plasma cell populations, as well as of the memory B cell populations that contribute to IgE memory. However, they have also led to differing conclusions that will require clarification from additional studies.

IgE plasma cells. Recent studies indicate that most IgE plasma cells are short-lived and that, in contrast to IgG1 germinal centre B cells, which primarily differentiate into long-lived plasma cells, IgE germinal centre cells are predisposed to differentiate into short-lived plasma cells. Indeed, studies using mice that have monoclonal B cells and T cells showed that there was a rapid differentiation of IgE cells into plasma cells28. In another study of in vitro B cell cultures from wild-type mice, a much larger fraction of IgE B cells differentiated into plasma cells compared with IgG1 B cells10. IgE plasma cells in Verigem mice10, M1 prime GFP knock-in mice9 and CεGFP mice21 that had been immunized with antigens or infected with N. brasiliensis were predominantly short-lived cells found in the lymph nodes and the spleen. Consistent with a predisposition of IgE plasma cells to be short-lived, transgenic expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 in the B cell lineage resulted in increases in both IgE plasma cells in the lymph nodes and IgE levels in the serum, because of the rescue of short-lived IgE plasma cells from apoptosis10. A comparison of the ratio of plasma cells to germinal centre B cells over time for IgE versus IgG1 in Verigem mice10 indicated a greater predisposition of IgE cells to differentiate into plasma cells than IgG1 cells, which were more likely to persist as germinal centre B cells. Similar differences in the plasma cell to germinal centre B cell ratio for IgE versus IgG1 were also observed in M1 prime GFP knock-in mice53. In addition, IgE B cells were found to express higher levels of the plasma cell differentiation factor B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (BLIMP1; also known as PRDM1)10. Furthermore, deletion of BLIMP1 resulted in a preferential increase in IgE germinal centre B cells compared with IgG1 B cells, which confirms the predisposition of IgE B cells to differentiate into plasma cells10.

A small number of IgE plasma cells have been detected in the bone marrow of Verigem mice10, M1 prime GFP knock-in mice9 and CεGFP mice21. In addition, other groups have detected IgE plasma cells in the bone marrow of wild-type mice and concluded that these cells are long-lived as they were resistant to irradiation58 and cyclophosphamide59, which are both treatments that eradicate upstream sources of cells, such as memory B cells and proliferating plasmablasts, that could differentiate into new plasma cells. Thus, although the majority of IgE is derived from short-lived plasma cells, a small population of long-lived IgE plasma cells that are located in the bone marrow can contribute to low levels of sustained serum IgE antibodies.

Studies of IgE and IgG1 plasma cells in wild-type and KN1 mice indicate that membrane IgE BCR signalling can affect the fate of IgE plasma cells48. In these studies, wild-type IgE plasma cells responded less efficiently to the bone marrow chemoattractant CXC-chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) than both wild-type IgG1 plasma cells and IgE plasma cells from KN1 mice. Furthermore, a much larger number of IgE plasma cells were found in the bone marrow of KN1 mice compared with wild-type mice. IgE responses in immunized KN1 mice were more robust and more sustained than those in wild-type mice, which is consistent with the increased generation of long-lived IgE plasma cells. It would be interesting to determine whether IgE germinal centre B cells in KN1 mice have lower levels of BLIMP1 than in wild-type mice, as this would strengthen the link between IgE BCR signalling and short-lived plasma cell differentiation.

In humans, in vitro B cell stimulation experiments also indicate a predisposition of human IgE B cells to differentiate into plasma cells60. IgE-secreting cells that are likely to be short-lived IgE plasmablasts and plasma cells have been detected in human blood and have been shown to correlate with serum IgE levels61, 62, 63, which suggests that, similarly to mice, a considerable proportion of IgE in humans may be produced by short-lived plasma cells. Marked seasonal increases and decreases in allergen-specific and total IgE levels have been observed in allergic individuals64, 65, 66. These changes in IgE levels over the course of several months are consistent with IgE production from short-lived plasma cells and are similar to the transient increases in IgE that are observed following the immunization of mice4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

By contrast, it has been reported that helminth-specific IgE is still detectable several years after the treatment and clearance of the original infection in humans, which suggests that long-lived IgE plasma cells may also be present in humans67. Consistent with this idea, there are case reports of the transfer of allergen-specific IgE to a non-atopic recipient following bone marrow transplantation, which supports the existence of bone marrow-resident long-lived IgE plasma cells68, 69. Taken together, it seems that both short-lived and long-lived IgE plasma cells can be generated in humans and that, at least in some cases, high levels of IgE can be derived from short-lived IgE plasma cells.

IgE memory B cells. Secondary IgE responses in mice occur more rapidly than primary IgE responses, which indicates that there are memory B cells that contribute to memory IgE responses. However, the identity of the memory B cells that give rise to memory IgE responses has not been clear. It is possible that IgE memory B cells and/or IgG1 memory B cells, through a secondary switch to IgE, can contribute to IgE memory. Early studies indicated that both IgG1 and IgE memory B cells may contribute to IgE memory responses70, 71, but definitive studies could not be carried out because of technical limitations.

Studies of mice in which either IgG1 or IgE B cells cannot be generated suggest that IgE memory primarily arises from IgE memory B cells and that IgG1 B cells are not required for IgE memory responses. In Δ5′Sγ1 mice and Sγ1-knockout mice, which do not generate IgG1 B cells, IgE memory responses are the same or increased compared to wild-type mice25, 26. By contrast, ΔM1M2 mice, which have normal IgG1 B cell responses but which lack the IgE BCR, completely lack memory IgE responses47. Consistent with a major role for IgE memory B cells in IgE memory responses, mice with alterations in IgE BCR signalling have altered memory IgE responses. KVKΔtail mice have normal IgG1 B cell responses but greatly reduced IgE memory responses47. Similarly, IgE memory responses are more robust in KN1 mice than in wild-type mice, whereas IgG1 B cell responses are unaffected48.

Using M1 prime GFP knock-in mice, a very small population of IgE memory B cells was recently identified after infection with N. brasiliensis or following immunization with TNP–OVA9, 20. These IgE memory B cells gave rise to memory IgE responses following transfer into naive B cell-deficient recipient mice that were subsequently challenged with N. brasiliensis. This was the first study to isolate IgE memory B cells and to assess their ability to contribute to IgE memory responses. By contrast, most IgG1 memory B cells did not give rise to memory IgE responses in cell transfer experiments9, 20. However, studies using M1 prime GFP knock-in mice did indicate that some IgG1 memory B cells can undergo a secondary switch to IgE and can contribute to IgE memory responses20. In these mice, a small population of IgG1 memory B cells, which comprises ~10% of all IgG1 memory B cells and can be distinguished from the other IgG1 memory B cells by the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) probably arising from membrane IgE transcripts that are not productively rearranged to the antibody V(D)J region, could produce IgE memory responses in cell transfer experiments20. Although these cells contributed to IgE memory responses, it was calculated that the majority of IgE memory arose from IgE memory B cells and not from the secondary switching of these IgG1 memory B cells.

By contrast, another group has concluded that IgG1 memory B cells, and not IgE memory B cells, are the major sources of IgE memory. Studies using mice that have monoclonal B cells and T cells showed that isolated IgG1 memory B cells could undergo a secondary switch in vivo to give rise to memory IgE responses following cell transfer28. In these studies, isolated IgG1-negative memory B cells did not generate an IgE antibody response. However, given that IgE memory B cells are only present at a very low frequency, it is likely that the transferred pool of IgG1-negative memory B cells contained extremely few or no IgE memory B cells. Therefore, these studies do not rule out a contribution of IgE memory B cells to memory IgE responses and do not enable a comparison of the relative contributions of IgG1 versus IgE memory B cells to IgE memory responses.

In an additional study, B cells from mice with monoclonal B cells and T cells that had undergone class-switch recombination — which were presumed to include both germinal centre and putative memory B cells — were isolated and transferred into naive irradiated recipient mice, which were subsequently challenged21; in this study, memory cells were not specifically identified using cell surface markers. No differences in antigen-specific IgE and IgG1 responses were observed following the transfer of a total class-switched B cell population versus the transfer of a class-switched B cell population that lacked IgE B cells; this indicates that IgE B cells did not considerably contribute to IgE responses. However, given that memory B cells were not distinguished or separated from germinal centre B cells, these studies did not specifically assess the contribution of memory B cells versus germinal centre B cells (which greatly outnumber memory B cells in this population) to IgE responses. Taken together, the studies of IgE memory in mice indicate that both IgE memory B cells and IgG1 memory B cells can give rise to IgE memory responses, but more work is needed to determine the relative contribution of each subset to IgE memory responses in vivo.

There are very little data about IgE memory B cells in humans. Although some studies have described IgE-positive memory B cells in the blood of healthy and allergic individuals72, 73, 74, the contribution of various memory B cell populations to memory IgE responses in humans is not well understood. Overall, very little is known about the memory B cell populations that contribute to IgE memory in either mice or humans. Further studies are needed to determine the contributions of IgG1, IgE and potentially other memory B cells, such as IgM memory B cells, to IgE memory responses.

IgE repertoire and affinity

Studies of antibody repertoire and affinity maturation can lead to insights into B cell isotype switching and the antigen selection history for germinal centre B cells, memory B cells and plasma cells. Studies in mice are consistent with extrafollicular and germinal centre pathways for IgE production, as well as with the transient generation of IgE germinal centre B cells. Sequencing of the IgE repertoire from plasma cells and B cells that were isolated from immunized mice revealed high levels of somatic mutations and oligoclonal expansion with clonotype restriction, which is consistent with antigen-driven selection of the IgE response and a germinal centre origin of IgE plasma cells75. IgE plasma cells showed higher levels of antigen-driven selection than IgE B cells, which suggests that the IgE plasma cell pool is selected on the basis of affinity for the antigen.

A role for the IgE BCR in the selection of high-affinity IgE antibodies was deduced from studies of mice with altered IgE BCRs (KVKΔtail mice), which generated lower affinity IgE antibodies than wild-type mice during a primary immune response6. This study also compared IgE and IgG1 antibody repertoires and found that in wild-type mice the IgE antibody repertoire was less diverse and of lower affinity than the IgG1 antibody repertoire and consisted of sequences that were distinct from those in the IgG1 antibody repertoire. These results were interpreted as showing that sequential class switching from IgG1 to IgE does not have a major role in wild-type mice. However, when a memory response was assessed in KVKΔtail mice6, the IgE memory antibody repertoire was related to the IgG1 memory antibody repertoire, which is consistent with a secondary switching of IgG1 memory B cells to generate IgE; this may have been detected in the KVKΔtail mice but not in the wild-type mice because of impaired IgE memory B cell responses in the KVKΔtail mice that result from impaired IgE BCR signalling.

In mice with monoclonal B cells and T cells that were repeatedly immunized, both IgG1 and IgE antibodies showed evidence of somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation28. However, at the same time point, IgG1 antibodies had more high-affinity mutations than IgE antibodies, with IgE antibodies attaining a comparable frequency of high-affinity mutations as IgG1 antibodies only after additional rounds of immunization. A similar observation was made by another group using wild-type mice, in which IgG1 plasma cells had more high-affinity mutations than IgE plasma cells late in the primary immune response10. In addition, in both wild-type mice and mice with monoclonal B cells and T cells, IgE plasma cells had fewer high-affinity mutations than either IgE or IgG1 germinal centre B cells10, 28. Taken together, these data are consistent with an early exit of most IgE plasma cells from germinal centres before considerable affinity maturation occurs, which is in contrast to IgE germinal centre B cells, IgG1 germinal centre B cells and IgG1 plasma cells, which may persist for a longer period in germinal centres and may accumulate more affinity-enhancing mutations.

Multiple studies of IgE antibody repertoires in individuals with allergic diseases show clear evidence of somatic hypermutation76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, but there have been few comparisons of IgG4 (which is the corresponding human isotype to mouse IgG1) and IgE repertoires. Comparative studies of IgG4 and IgE repertoires in non-allergic and allergic individuals79, as well as in individuals with parasite infections81, showed significantly fewer mutations that are indicative of affinity maturation in IgE antibody complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) than in IgG4 antibody CDRs. These results are similar to the observations in mice that the IgE repertoire has a lower frequency of high-affinity mutations than the IgG1 repertoire. The lower affinity of the IgE repertoire may help to prevent undesirable anaphylactic reactions by competing with high-affinity IgE for binding to mast cells and/or by being inherently less cross-reactive to innocuous antigens34, 82, although some studies indicate that low-affinity IgE antibodies can facilitate mast cell activation83.

Factors regulating IgE clearance and homeostasis

Recent studies have provided new insights into IgE homeostasis, uncovering new roles for FcεRI and FcεRII in the capture, the clearance and the regulation of serum IgE levels in vivo.

It has been suggested that IgE receptors may contribute to the regulation of serum IgE levels84, 85, 86, but no differences in the rate of clearance of IgE from the blood have been observed in FcεRI-deficient or FcεRII-deficient mice87, 88, 89. However, a role for human FcεRI on dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages in IgE clearance was recently described90. It was found that FcεRI on human dendritic cells and monocytes, but not on basophils, is constitutively internalized and that the bound IgE is endocytosed and delivered to lysosomes where it is subsequently degraded. These observations were confirmed with the use of transgenic mice that express the IgE-binding α-subunit of human FcεRI in their FcεRI receptor complexes90. This newly described role for human FcεRI in IgE clearance was not previously observed because it requires the constitutive expression of FcεRI on macrophages and dendritic cells, which occurs in human cells but not in mouse cells. Of note, studies of the low-affinity receptor IV for IgG (FcγRIV), which is a newly identified mouse Fc receptor, indicate that it may be the functional orthologue of human FcεRI in mouse macrophages91, 92 and thus it would be interesting to determine whether FcγRIV contributes to the clearance of IgE in mice.

Another study assessed the role of FcεRII in regulating IgE levels in vivo by using B cell-deficient mice and an antibody that blocks IgE interactions with FcεRII. These studies found that, although FcεRII does not mediate the clearance of IgE from the blood, it reduces the levels of free IgE in the blood by functioning as a sink on cells to bind a substantial portion of the total IgE antibody pool87. Thus, in addition to the previously described functions of FcεRII in regulating IgE production following IgE-mediated activation11, FcεRII has a role in regulating IgE levels in vivo by passively binding to IgE to reduce free IgE levels in the blood.

IgE also binds to FcεRI on tissue mast cells, which use this IgE to survey antigens and to trigger mast cell activation. It has been assumed that tissue mast cells passively acquire IgE from the blood following the diffusion of IgE across the vascular wall, but this had not been carefully assessed in experimental studies. A recent study revealed that perivascular mast cells in the skin extend cell processes across the blood vessel wall to actively acquire IgE from the blood93. These studies suggest that the positioning and the access of tissue mast cells to the vasculature may influence the efficiency of blood IgE sampling and that IgE-binding cells in the tissues, such as mast cells, may have developed ways to actively sample the blood to ensure that the antigen specificities of transient IgE antibody responses are appropriately captured and displayed on their cell surfaces over extended periods of time.

Conclusions and perspectives

There has been considerable progress in recent years in understanding the production and the regulation of IgE in vivo, which has primarily been driven by the use of genetically modified mice and mice expressing reporter proteins. Taken together, these studies lead to the following model for in vivo IgE production and regulation (Fig. 3).

IgE is produced through both extrafollicular and germinal centre pathways. Early IgE responses are of low affinity and arise from extrafollicular sources, whereas late IgE responses are of high affinity and arise from germinal centres. Direct and sequential class switching to IgE in germinal centres results in the generation of IgE germinal centre B cells and plasma cells, but the majority of these cells are short-lived, which creates an inability to sustain most IgE responses. However, a small number of long-lived IgE plasma cells are produced and migrate to the bone marrow, where they contribute to sustained IgE antibody production.

The fact that IgE responses are predominantly short-lived may limit the generation of potentially pathogenic IgE during a normal IgE antibody response; for example, more sustained IgE germinal centre reactions could lead to the generation of higher affinity IgE antibodies that might cross-react with normally innocuous antigens, as well as to the production of more long-lived IgE plasma cells that would contribute to higher sustained levels of IgE in the body, which would ultimately lead to a greater likelihood of triggering inappropriate anaphylactic reactions. The transient nature of the IgE response is further reinforced by the fast clearance of free IgE from the blood, which is partly driven by FcεRI-mediated endocytosis in macrophages and dendritic cells in humans. In addition, low levels of free serum IgE are partly maintained by an FcεRII sink on B cells in mice. Perhaps to ensure that mast cells effectively sample ongoing IgE production given the transient nature of IgE responses, perivascular mast cells in the skin actively extend processes across the blood vessel wall to survey and to acquire IgE.

Several features of IgE responses are still poorly understood. First, the fate of IgE germinal centre B cells is not clear. Various groups have suggested that these cells differentiate into IgE plasma cells and/or IgE memory B cells, or that they are non-productive cells that undergo apoptosis, although these fates might not be mutually exclusive. Second, the sources of IgE B cell memory are controversial, as different studies have led to opposite conclusions regarding the contributions of IgG1 and IgE memory B cells to IgE memory. Third, the role of direct and sequential class switching in IgE responses remains unclear, as some studies suggest that sequential class switching is the primary route for the generation of IgE plasma cells and IgE memory, whereas other studies indicate that IgE responses can still persist in the absence of switching to IgG1, although the quality may be altered. More detailed single-cell analyses of IgE cell repertoires and class-switch history, as well as potentially generating dual reporter mice that mark both IgG1 and IgE class switching, may help to clarify these issues. Additional studies are also needed to further examine the contribution of the newly described alternative sequential class-switching pathway to IgE production in wild-type mice.

Finally, there are very limited data on the production and the regulation of IgE in humans. Although the available data are mainly consistent with the studies of IgE biology in mice, additional studies are needed to assess the contribution of short-lived and long-lived plasma cells to human IgE responses, as well as to assess the sources of human IgE memory. A better understanding of IgE biology may lead to new approaches to treat allergic diseases, including potentially inducing long-lasting changes to allergic sensitivities by modulating IgE production and memory.

Nature Reviews Immunology | Review

Lawren C. Wu1, & Ali A. Zarrin1,

Nature Reviews Immunology | Review

Lawren C. Wu1, & Ali A. Zarrin1,

Nature Reviews Immunology (2014) Volume: 14, Pages:247–259

IgE is secreted and expressed on the surface by B cells. In short, IgE is anchored in the B cell membrane through the transmembrane domain, and the membrane domain of the membrane linked to the mature IgE molecule through a short film binding region. Know more application of transgenic animals related to IgE at http://www.creative-animodel.com/Animal-Model-Development/Transgenic-Animals.html

ReplyDelete